TRADITIONAL MUSIC

The traditional music of St. Lucia is remarkably rich in its variety, but very little is known. St. Lucia is famous in the Caribbean for keeping alive its oral traditions, one of which is its musical life and great variety of artistry on the island.

The language and the music reflect the influences of its colonial history. Some musical instruments played in St. Lucia such as the violin, the guitar, and mandolin, cannot be dissociated from their European and African influence. Others such as the Ka, also called Bélè drum, which is a hollow, barrel-shaped drum held between the legs in a sitting position and played with bare hands.

Other percussion includes the Baha (long, hollow tube blown like a trumpet to produce a percussive sound), the Chak-Chak or the (rattle), the Zo (bones), and the Gwaj (scraper) are viewed locally as part of the African heritage.

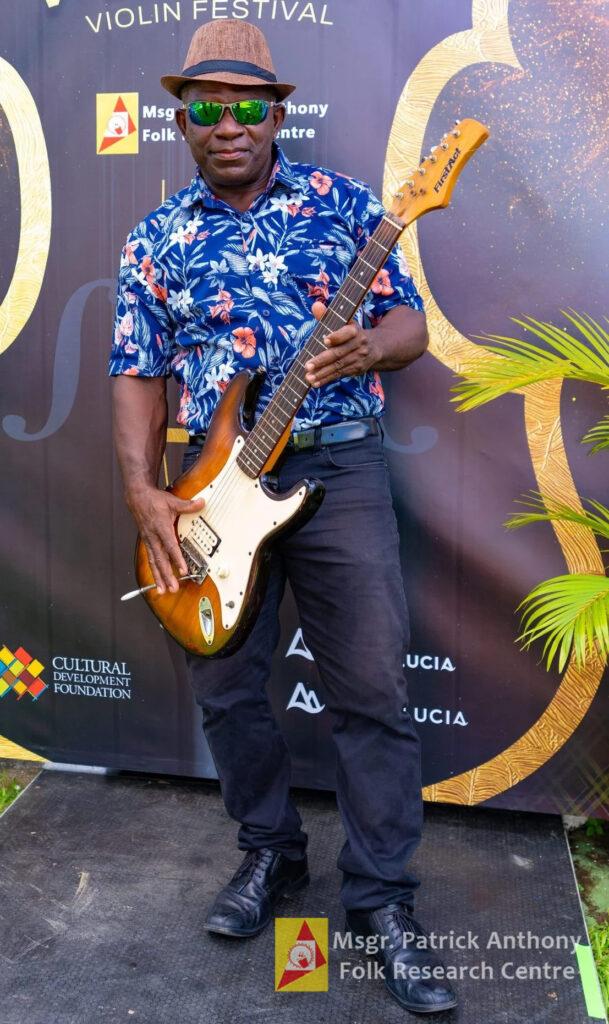

Augustin “Charley” Julian

STRING INSTRUMENTS

BANJO

Two different types of banjo currently exist in St. Lucia. The older model is called Banjo Bwa Pòwyé (Cedarwood banjo). The body is made of bwa blan (Simaruba Amara), plywood, or aluminum.

The other type of banjo is known as the Screw or Skroud Banjo.

The placement of the screws differentiates one instrument from another. The screws of the Banjo Bwa Pòwyé are at the top of the circle while those of the screwed banjo are around the circle.

The banjo was formerly used during Carnival but this tradition seems to have died out nearly 40 years ago. At that time, the banjo gave accompaniment to a saxophone, along with a drum and chak-chak, and sometimes there would be two banjos.

HOW TO PLAY

The banjo player, like all other St. Lucian musicians, learns to play by ear, listening to and observing other players. Except in very rare cases, there is no explicit apprenticeship. Yet if a musician is off (whether in harmony, rhythm or even musical style) he will quickly be told so. The more experienced players will help him get the “feel” by singing him the melodic line, the idea being that the simple fact of making him remember the main melody will be enough to pull everything into place.

THE RHYTHM

The banjos of St. Lucia are played, according to the context, in picking or strumming style. When the musician is alone, he will more often pick, whereas if he is accompanying a scribed thus: a lead singer sings the first chorus unaccompanied, which is then brought in after every couplet. The tambourine and chak-chak provide the rhythmic accompaniment while the banjo and other string instruments provide the harmonic support for the singers. At a Séwénal, the banjo is used with a violin, a guitar, a chak-chak, and a bonm (an old pan dented in the bottom). The favourite styles played on this occasion are the ‘hot’ dances like the maynan.

QUATRO

The St. Lucian Quatro is a four stringed instrument which has the same form as that of a guitar but is smaller in size. Its tuning corresponds exactly to the tuning of a four stringed banjo in using the following pitches: – A, D, F# and B.

The fabrication of a quatro requires several qualities of wood. As is the case for many other St. Lucian instruments, most of the Creole terms for instrument parts are taken from the vocabulary of different parts of the human body.

GUITAR

The Guitar does not need any particular description. The six-stringed instrument follows the norms established by the traditional guitar. It is very often used in St. Lucian musical performances.

The Guitar always supplies the bass line in the ensemble playing at a quadrille dance. In order to obtain a clear and loud sound, the bass line is always played in the picking style with a plectrum.

Only in the context of Séwénal songs, abwé songs (drinking songs at Christmas), and calypso songs, does the guitarist play in a strumming style. The instrument, then, provides a full harmonic support to these three types of songs.

VIOLIN

The Violin in St. Lucia is linked to the western violin and does not need any specific description.

VIOLIN MUSIC

Violin music in most instances is associated with Kwadwil dance. In the past, the dance tradition was seen as out of fashion, but several years after independence in 1979, however, the tradition was seen as a reproduction of a European dance and has since been transformed to the point of acquiring an entity of its own, now distinctively St. Lucian, because of its constant “détaché” style of violin playing.

Most kwadwil evenings are organized by one person and performed at a private house or a rented hall. Invitation cards specifying the location, date, hour, and fees are sent to the invitees. The number of guests is limited to the number of dancers required for the event, that is, eight or twelve coules.

The Musicians, essential for the performance to take place, are hired by the organizer and are paid. Except during the Lenten season, a kwadwil evening can be organized at any time during the year. However, since during the rainy season the entire evening might be cancelled because of bad weather, the favourite times are during the dry season January to June.

The choreography of kwadwil had to be learned, memorized, and practiced before being performed. These three different stages of apprenticeship, which did not correspond with the usual norm of “learning-through-doing,” were highly valued, and still is today. When performed correctly, it was traditionally thought to demonstrate control over behaviour, decency in manners, and skills to reflect special values that had been traditionally linked with a higher social class. They symbolized a particular type of knowledge believed by many to be of higher quality and of a more complex nature than the other local traditions.

Chak-Chak

The Chak-Chak, also called Pann, is a percussion instrument in the family of the shakers. This instrument was traditionally made of a metallic kerosine container or of any other type of pot, which was cut and welded in the form of a long tube and filled with dry seeds or pebbles. The two types of dry seeds most used are the gwenn légliz and the gwenn maloubi.

The metallic tube is pierced with small holes all over its surface so that it can produce a loud sound. The quantity of seeds and the number of holes depend entirely upon the maker’s personal preference for a particular sound of chak-chak.

CREOLE MUSIC

Creole is the oldest style of music heard in St. Lucia, and unfortunately, like many aspects of St. Lucia’s cultural heritage, it seems to be a fading art form. Creole is played by Chak-Chak bands that feature a violin, guitar, banjo (called a quatro) and a couple of African style drums called Tanbou, which are made locally.

The music generally is ¾ time sounding much like an upbeat waltz. A few Chak-Chak bands still play on the island, particularly in the South. A traditional local style, called Quadrille, is danced to the music in very colourful time-honoured Creole apparel. A few resorts still feature Chak-Chak bands for guest entertainment.

Tanbou

CARNIVAL

LA ROSE MUSIC

During La Rose sessions and on the feast day itself, the banjo is accompanied by a tambourine, a baha (a long, empty tube used as a percussion instrument) and a chak-chak.

Sometimes, when available, a guitar and quatro are added to the ensemble. A La Rose musical performance may be derille – as well as the closed coupe dances like the polka, the widova and lakonmèt.

La Rose Session

BEACH PARTY AND GAME SONGS

A play-song-dance in St. Lucia is an entertainment and an opportunity to demonstrate skills and to make public commentaries. St. Lucians “play” through singing, playing musical instruments, dancing, acting out their songs, or telling stories.

The play-song-dances in Saint Lucia include four musical genres, namely débòt (also called djou), yonbòt, solo, and jwé pòté. All four are employed when it is available with the ka drum, and occasionally, the tibwa (a pair of sticks played against the rim of the drum) for their musical accompaniment.

1. Débòt – “Isabel-o” – Song

The dancers do not go round the circle before the dance properly begins, they immediately dance the débòt proper (as is often the case) by hearing the drummer play a vap sound (that is, a damped sound, even though it is not always very accentuated in this selection) on the first beat of each phrase to signal the dancers to perform the blòtjé figure.

2. Solo – “Byen, Byen Elford Mayé”

This song employs the verbal tactic of lang déviwé. This technique consists of saying the opposite of what one really means. For the singer of this song or dance about how well he is married is very ironic when everyone knows that he and his wife now live separated.

At the beginning of his song, the singer invites in a spoken voice four couples (kat kavalyé, kat danm) to dance. The drummer signals to the dancers when to yield their place for other couples to take their turn; by two series of five well-marked strokes of identical pitch and duration which stop the entire movement and allow the new dancers to get in position to begin their dance.

3a. Jwé Pòté

Play-song-dances are mostly performed by people living in the countryside. Everybody, from children to adults, is welcome to ‘play’. Although Saint Lucian ‘play’ might be enacted on any occasion and be invoked for any reason, the beach parties, full moon gatherings, and débòt evenings are designed especially for the performance of ‘play’.

Sometimes a private person organizes a débòt for his own pleasure or, as is often the case, it is organized by the owner of a rum shop of a bar who wants to make money through the sale of drinks. Organizing such would then consist of hiring a drummer and a song-leader for the evening. The salaries he gives the performers are usually meager, but he offers them plenty of free drinks and food. The dance normally takes place in a clear space near the rum shop or by the house of the private organizer.

The texts of the four play-song-dances most often report events well known to the participants and can focus on sex, human relationships, and personal miseries. Since the song-leaders allow themselves to say things about people that could not be said otherwise, the use of the label “play” for these types of songs is in fact most convenient:-

- It not only frees the singers from many social conventions but also protect them against reprisals by the church or the laws.

However, to further protect themselves from getting into trouble, the song-leaders typically use verbal tactics in their texts, such as lang déviẃé (saying the opposite of what you really mean; metaphor (using a word to refer to something else) consciously omitting certain names or parts of the story.

3b. Jwé Pòté – “Ki Bèl Bato” Song

A drummer is not always available when people decide to play on a full moon evening. The song is then simply accompanied by clapping hands. The lyrics are based on only a few words, such as Look at the boat. Every time dancers hear the ostinato pattern based on the words “adan’y” (on board) sung by the choir, they perform a blótjé. This is thus a fast-paced dance.

4. Jwé Pòté – “Mangotinn Lababad ka Bwilé” Song

This song is about two people who have been sexually teasing one another, while the mangotin lababad (a dessert made of mangotin) was being prepared but is now burning. This jwé pòté can be performed as described above or by a group of couples in a circle, men and women facing each other. They sway their bodies back and forth on each beat and reproduce the actions referred to in the lyrics: hold me by the neck for us to see, hold me by the waist for us to see.

The song continues by referring to the leg, the thigh, and then the whole body. When the singer sings “ay yay yay…,” the dancers change partners, and the game starts over. The distinctive, guttural timbre of the singer (who is also the drummer) combined with his expressive inflections are used to enhance the liveliness of the performance.

SEASONAL MUSIC

The Chanté abwè (drinking songs), rarely heard nowadays, were songs performed mainly during the Christmas season on evenings called Wibòt. Friends formed a group and everyone took turns both receiving the others at their home and paying for the food and drinks. The singing was organized as a game whereby everyone sitting at the long table placed in the middle of a room had to sing a new song every time around.

There was no musical accompaniment at a wibòt. The entire performance relied on complete participation, since every two lines of text sung by the singer were repeated by the group. The songs were distinguished by their texts, which are actually composed of old French words mixed with Creole expressions.

Séwénal and Masquerade are celebrations organized around holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s Day and Easter. The ensemble includes the same instruments used in merry-go-rounds, cockfights, and séwénal. The musical genres played in both the masquerade and séwénal were the same: Merengue, March and Maynan (another name for Manpa, a fast and lively dance).

A tanbou tenbal (a large, barrel-shaped drum covered at both ends by a skin stretched by cords and held on the side by a strap passed around the player’s neck and struck by a stick covered by a piece of cloth), a snare drum called a kettledrum, a chak-chak, and a bamboo flute.

This is usually performed during the night or at dawn, during the two weeks of Advent and except for Lent, at any other time of the year (example, Sundays, full-moon evenings, or during Christmas). No one wears a mask or costume. It is organized solely for pleasure and consequently with no hope of earning any money.

Masquerade

The musicians leave early in the morning to play, sing, and dance. While they walk around playing their instruments, two costumed male dancers, one playing a woman’s role (female mas), the other – a man’s (male mas), cheered up the crowd by performing incredible contortions.

Besides performing for entertainment, the group also aimed to earn some money through voluntary donations from the spectators.

KOUTOUMBA

Koutoumba or Katumba is a unique song-dance found in the village of La Grace, Laborie and Piaye. The ritual was only performed for the death of a Djiné, a person descended from Africans who came to the island in the middle of the 19th century.

KÉLÉ MUSIC

Kélé is a religious tradition that is associated with a small group of people from the Babonneau region, who call themselves Djiné (Djiné refers to groups of people descendants from Africans who arrived on the island around the 19th century).

The tradition is unique to St. Lucia, it is strongly connected to the Ogun Festival in Nigeria, even though kélé is concerned not only with one deity, but with three (Ogun, Shango and Eshu) (Anthony, 1986: 114).

The Catholic Church rejected the tradition until the early 1960s, where it has been practiced underground since its introduction in St. Lucia. It was held on the “first Sunday in the New Year, the Sunday before Lent, the first Sunday in October and the last Sunday in November,” (Harmsen, Ellis, Devaux, 2014:210), or the anniversary of the death of a recent ancestor” (Crowleyl, 1957:8) or given to ask the African ancestors for protection in all matters of importance, including “good crops, good health, and good fortune” (Simpson 1973:110).

Only one family from Resina, Babonneau, holds Kélé and “claims to have authority to perform the ritual and to pass on that authority to their kin (Anthony 1986:106).

The ritual includes the display of smooth stones (Shango’s worship emblem) and of iron-and-steel tools (in honour of Ogun), the washing of the ram goat to be offered to Shango, the smashing of a calabash at the end of the ritual (to appease the Yoruba deity Eshu, prayers and incantations mostly addressed to Ogun, eating, singing, dancing, and the playing of two drums called tanbou manman (mother drum; a large, double-headed drum played with one stick) and tanbou ich (child drum; a long, narrow, cylindrical wooden body, covered at one end by a skin and played with one stick). These two drums, used only during the ceremony, played four different song-dance rhythms – kogou, èrè, kèrè and adan – each of which is played at a specific moment during the ceremony.

WORK MUSIC AND SONGS

Chanté siyé are work songs that accompany woodsawing. Performed by a song leader and usually no more than two responders, they are typically accompanied by the ka drum and a pair of tibwa.

Instead of holding the barrel-shaped drum in an upright position, the player lays the instrument on the ground and sits on the barrel while playing on the single skin with his bare hands. The pair of tibwa are played against a bamboo tube or wooden log resting on a stand. A technique that is associated with the Martiniquan style of playing.

Extracts of a study published in 1984 from research done in St. Lucia by Joycelyn Guilbault, a Canadian musicologist. The study is entitled, “Musical Events in the Lives of the People of a Caribbean Island St. Lucia”