SOCIAL HISTORY OF CREOLE LANGUAGES

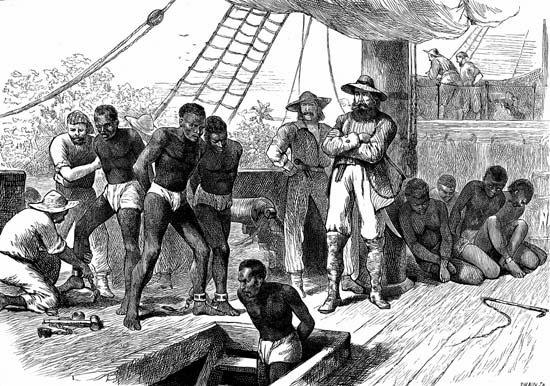

Creole languages, perhaps more than any other language type, are closely tied to the societies in which they were created and are at present used. They may be due to the fact that their very origins were created as a result of social pressures, that is the social pressure for communication between ethnic groups who did not understand each other and so developed a pidgin (the first stage towards the formation of a creole) for the inter-ethnic communication. In the case of the Caribbean Creole, the social pressures for communication were mainly between African and European ethnic groups. The social context for the Caribbean Creoles was the Atlantic Slave Trade, involving the enslavement of Africans by Europeans for economic profit.

As well as being a social context for exploitation, however, the Caribbean Creole social context is one of the African resistance, readaption, and perpetuation of African culture in the teeth of an attempt to enforce European culture upon captured Africans. Out of this social carthesis of African cultural continuity in the New World, was born the Caribbean Creole Languages as an embodiment of the history and social context of its speakers.

Captive Africans being transferred to ships along the Slave Coast for the transatlantic slave trade, c. 1880.

Photos.com/Getty Images

Historical background: The development of Patwa in St Lucia’ situates the development of Creole in St. Lucia within such a socio-historical context between 1639 and 1948. With a particular emphasis upon the contribution of nineteenth-century St Lucia maroons to the development of St Lucia Patwa. ‘The social history of the Caribbean languages: the St Lucian case’, while accepting the historical background of St Lucia as having a predominating effect upon the St Lucian Creole language (Patwa), also analyses the modern relationships between language and society in St Lucia, many of which have attributable historical causes.

Maroons

‘Creoles and ideologies of return’ examines further the different political ideologies which have resulted from the different social histories of three Creole societies, in Casamance (Senegal) Gambia, and St Lucia. The use of each Creole language as a social symbol is also outlined

This analysis is taken further in ‘Portuguese Creole in Casamance, French and African Languages: languages in competition in southern Senegal’. In this chapter, social conflicts inherent in the creation of this Portuguese Creole are also evident in this present-day development.

The large extent of overlap between social conflict, language change, and creativity in Creole languages suggests a model of language competence and cognition in creoles in which social conflict, involving languages in competition, are themselves, central to the language and cognitive competence of creole speakers.

Source: unknown